This post may contain affiliate links. Every link is hand-selected by our team, and it isn’t dependent on receiving a commission. You can view our full policy here.

For months, 3 a.m. attacked me. Every night, I’d wake up in the middle of the night, at first peacefully, and then the dread would wash over me like a chest-seizing terror, as I found myself grateful for my husband, my kids, my life—and wondering when it’d all end. I’d suddenly imagine death through the lens of losing consciousness; of not experiencing another thing in this world, not even being aware of my passing. That fade to blackness scares me most of all.

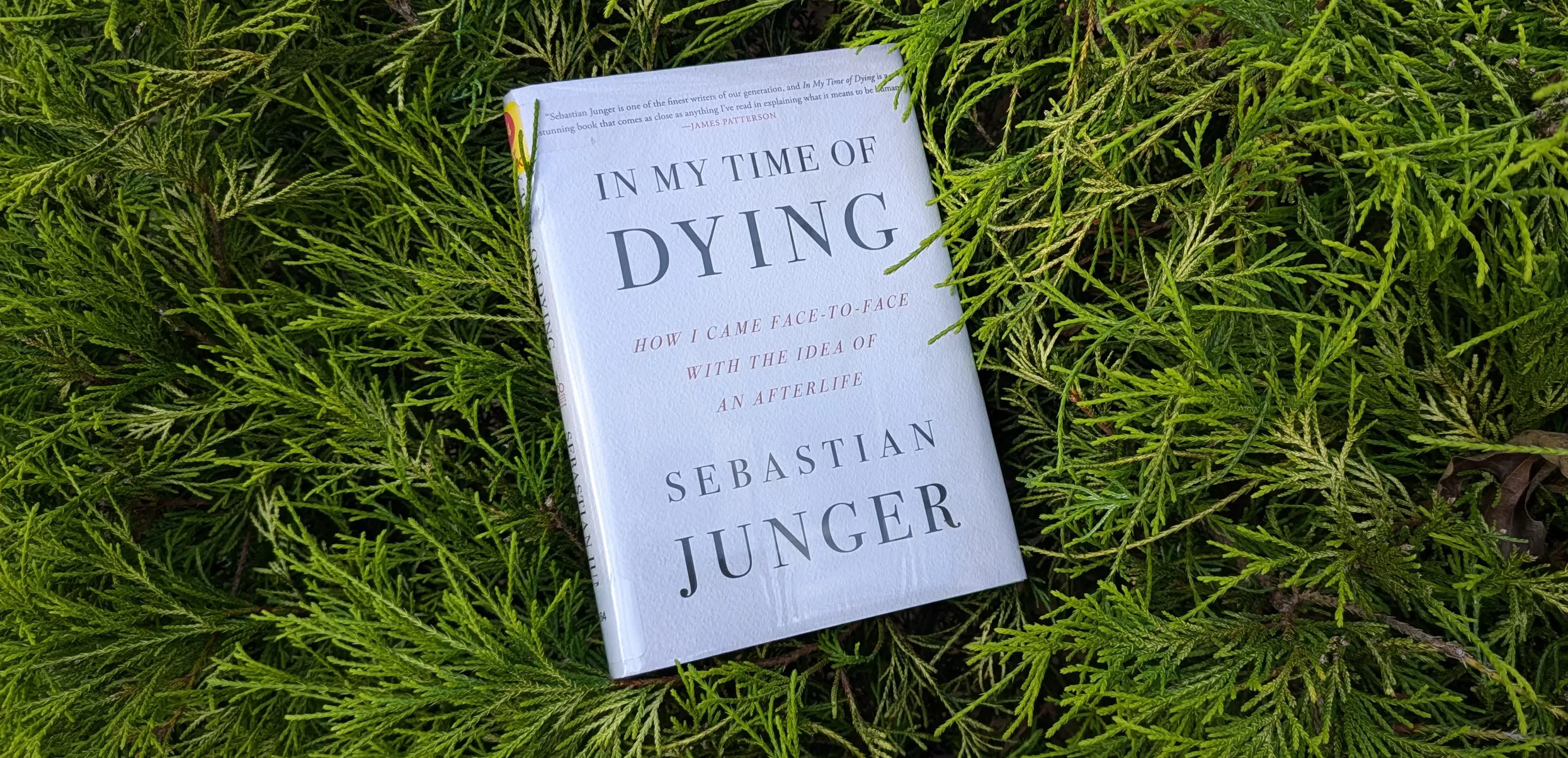

Despite being a Christian, I grapple with the thought of heaven and the afterlife. I so desperately want it to be real, yet my rational, skeptical mind questions it. And so, when I passed Sebastian Junger’s In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face-to-Face with the Idea of an Afterlife at the library, I had to scoop it up. And, despite having four books ahead of it in my “to read” queue, I devoured it in just a few days.

Junger’s book is described as “part medical drama, part searing autobiography and part rational inquiry into the ultimate unknowable mystery” of what happens after we die. The author—a war reporter, Peabody Award winner and New York Times bestselling author (you might be familiar with his book, The Perfect Storm)—shares how, despite several brushes with death in war zones, he nearly lost his life on an otherwise mundane afternoon in June 2020. Junger shares how a gripping abdominal pain sent him to the ER, and how doctors raced to figure out what was wrong—and how to save his life—as the odds stacked against him. He survived, almost miraculously, though at one point, he found himself staring at a black void on his left, and a vision of his deceased, atheist father overhead, calmly telling him he could stop fighting and join him on the other side.

Our individual experiences are an illusion that conceals the ultimate reality of one great consciousness.

— Sebastian Junger, paraphrasing Erwin Shrödinger

The experience prompted Junger to explore why he had such a vision, as well as what might cause deathbed visions and near-death experiences in the first place. This isn’t an “I had a vision, so ghosts and heaven are for real!” story; Junger takes a very technical approach. He pores over others’ accounts, along with medical and scientific research, weaving in theories on physics and debates over consciousness, exploring studies involving photons and digging into debates on whether they’re all just hallucinations or temporal lobe seizures or whatnot.

And, if there is an existence after death, he posits, how could that work, rationally speaking? This sets us on deep dive into physics and theories of reality, and one of life’s biggest mysteries: consciouness. Or, more specifically: What is consciousness, and how did it come about? Can it be destroyed?

After exploring several theories, he shares Erwin Schrödinger’s proposition that, in Junger’s words, “our individual experiences are an illusion that conceals the ultimate reality of one great consciousness.” Schrödinger backs this up with how many mystics, across centuries, have independently arrived at this conclusion. We are all made of stars, as Moby might say.

“In such a world, consciousness could never be lost because it’s part of the cosmic fabric, and my father as a quantum wave function could welcome me back to the great vastness from which we all come,” Junger writes.

Strangely, thinking of those who have passed as quantum wave functions resonated with me and provided a sense of comfort. (Yup, I’m aware of how that sounds.) While Junger ultimately concludes that we don’t have enough information to have a definitive—or even a strong—answer to these questions, it’s oddly empowering to explore them head-on. To face those dark questions and accept that there are some things you don’t know, and that just because you can’t scientifically confirm the best-case scenario (heaven) doesn’t mean you’re condemned to the absolute worst fear either. And that not knowing is okay, too. And, I’d add, that faith requires not having all the answers and accepting that you are not omniscient, and that you do not need to be. (Which, at the end of the day, I think is part of that existential dread—we all have main character syndrome and want to write our story forever and ever and ever, amen.)

The book reminded me of what got me through that bout of 3 a.m. existential crises: What you have is this moment. Experience this moment.

I’d bring myself back to the present, and I’d find a swelling of gratitude for being alive and conscious and experiencing this moment—even the brutal parts. Because, as cheesy as it sounds, the more I worry about the eventual, inevitable unknown, the more I rob myself of now. And if life is made up of the present, why dwell (especially negatively) anywhere else?

I don’t know it all, but I know one thing for sure: I will fully absorb this moment as much as I can.

You can pick up a copy of In My Time of Dying on Amazon and at most major bookstores.